- Home

- Stephanie Ricker

The Star Bell (The Cendrillon Cycle Book 3)

The Star Bell (The Cendrillon Cycle Book 3) Read online

The Cendrillon Cycle

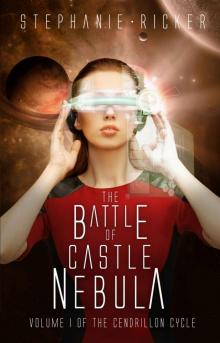

Volume I: The Battle of Castle Nebula

Volume II: A Cinder's Tale

(published in the Five Glass Slippers anthology)

Volume III: The Star Bell

© 2016 by Stephanie Ricker

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—for example, electronic or recording—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in reviews.

This volume contains a work of fiction. Names, characters, incidents, and dialogues are products of the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Cover design by A.E. de Silva

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

About the Author

To Anne Elisabeth,

for spurring me on to write more and write better, and for providing the enthusiasm and motivation when I had none of my own.

The expanse was the most unsettling part of the experience. That surprised her; she thought that growing up on the seemingly limitless snowfields of Anser would have prepared her for the vastness of space. But it seemed that nine years of mining, working in mining coaches and living in narrow-halled space stations as a cinder, had squeezed her childhood tolerance for immensity right out of her.

Elsa’s gloved fingers clutched one of the halyards of the Sovereign’s port mainsail as she strove mightily to get control of her breathing. This was embarrassing. Another rigger blasted past her, using the maneuvering thrusters attached to his suit to zip over to a farther section of sail. The rigger braked with an abruptness that made Elsa catch her breath, slowing himself the second before he smacked into the sail. He tipped his feet in front of him just before making contact with the cendrillon yardarm, and his magnetic boots sealed to the material, anchoring him in place. With the perfect nonchalance of over-familiarity, he proceeded to rummage in his ditty case for tools as he floated, suspended by the boots for a moment before jackknifing himself back around to work on a portion of sail.

Elsa swallowed down her nausea and gripped the halyard even more tightly. Stars above, she had no business out here. This was madness. She longed for the familiar controls of a mining coach. Hell, at the moment she would even look forward to seeing the cantankerous Nebraska again if it meant the end of this stomach-churning experience.

From her vantage point partway up the halyard, facing away from the Sovereign’s port hull, she could see the rest of the port mainsail spread out ahead and above her like a giant wing. The Sovereign had six sails and was considered a triple-masted ship, with a fore, main, and mizzen mast on either side of her hull. The Casimir sails were typically retracted backwards when not in use, but riggers—like the daredevil whose antics were still making Elsa’s stomach roil—swarmed out onto the sails whenever repair or maintenance was required. Frigate rigger crews had to be able to perform their own sail repair if needed, since many drydocks weren’t large enough to accommodate the unfurled sails of the massive ships.

Beyond the sails, there was only space. Endless, mind-shatteringly huge, empty space.

When Elsa had accepted Karl Tsarevich’s offer to leave cendrillon mining behind and join the Sovereign’s crew, she had been warned the work was hard. No problem. She was used to hard work.

What she was not used to, however, was being too terrified to work.

Today she’d managed to get partway up the halyard to the lower main topsail, the section she was supposed to be maintaining. It was farther than she’d managed to get before during her first weeks as a rigger, but she couldn’t will herself to take another step.

She took a deep breath instead and tried to cajole herself into moving. “Get it together, Vogel,” she whispered to herself. “You’re not going to fall.” She inched her hand a little farther up the spun-cendrillon halyard, one of the lines gracing the mainsail to which the riggers clung.

The movement snagged the strap of her ditty case, causing it to slip, and she watched in dismay as the case containing her tools drifted away from her, slowly falling into emptiness. She gritted her teeth and lunged for it with one hand, catching the strap. She slapped the case against the yardarm and magnetized it there, which was what she should’ve done in the first place, and tried to get a hold of herself.

She didn’t care that her lifeline was securely clipped to the halyard, that her magnetic boots kept her feet firmly pressed to the yardarm holding the sail outstretched, that the rigger crews were kept under constant view and comm surveillance by the bosuns, or that the pack on her back contained thrusters to help her maneuver wherever she needed to go. No matter how many safety precautions she knew were in place, nothing could drown out the voice in her head screaming at her that she was about to fall, just like her ditty case. And, the voice shouted, the danger was not merely in plummeting downwards: she could fall in any and all directions. There were just so many ways to get lost in that vastness.

The entire universe, it seemed, was spread out in front of her, and she couldn’t shake the conviction she was about to pitch headlong into it.

Her helm commline activated, startling her with the sudden noise coming from the microphone near her ear. “You all right out there, girl?” a gruff voice asked. “You haven’t moved in five minutes.”

Elsa let out a shaky breath, relaxing her death grip on the yardarm. Bruno’s voice was a tether bringing her back to herself, safer and more sustaining than the physical lifeline that cabled her to the halyard.

She was about to say that she was fine, but such a statement was stupid. She clearly wasn’t, and the work wasn’t going to get done—at least, not by her, not today. “I’m not doing so well, Bruno,” she replied, voice wobbling in a way that would be most humiliating if she were talking to anyone she trusted less. “I’m…” She let out another breath. “I’m, uh…I’m too scared to move any farther.” The confession was wrung out of her, but she knew she wasn’t going anywhere without help. She despised that feeling. She had always hated being the newbie, but she hadn’t felt this way since her first days as a cinder, mining on Rhodophis.

Now, as then, Bruno was the one to make sure she was safe.

“Don’t you worry. I’m sending Marraine over to give you a hand.” The line went quiet for a moment, presumably as he was giving instructions to Marraine via her own commline. Bruno’s new role as bosun kept him inside the Sovereign rather than out on the sails for the most part, but he saw and heard all, watching over the rigger crew and orchestrating their maneuvers.

Bruno came back on the commline. “She’ll be there in just a bit,” he told Elsa. “So you were afraid of heights and just never knew it, huh?” The humor in his voice was warm and friendly, not judgmental.

Elsa managed a chuckle. “Never had occasion to find out,” she said, her voice still sounding breathless to her own ears even as she felt herself relaxing a little bit. “I’ve never been loose in space before this week. Not when a frighteningly thin spacesuit is the only thing between me and vacuum, anyway.” The soft whisper of the carbon dioxide scrubbers in her helm was reassuring. When she was a miner, she had gone months at a time without even noticing it, but here the breath-like sound of the suit’s machinery purifying her own personal atmosphe

re seemed loud in her ears.

Bruno didn’t laugh at her, and his tone was still patient. “You wore a suit when you were mining; that’s not really so different,” he reasoned. “Lots of people would find it frightening to be in a mining coach with lava all around, but that didn’t faze you. This is a stroll on a space station by comparison.”

Elsa snorted. “Yeah, well, lots of people can come and do this job for me, then, and I’ll stick to the lava, thanks very much.”

Bruno chuckled. “Hang tight. Let me check on where the Strelka’s riggers are.” He clicked off the commline to coordinate with another team, and Elsa tried not to feel bereft.

She twisted her head, seeking something to distract herself from the yawning expanse around her and the matching feeling in her gut. Counting the seconds until Marraine arrived wouldn’t make her fay friend move any faster.

The frigate Strelka hung in space near the Sovereign, close enough that Elsa could look across the intervening space to the other ship and make out the occasional tiny figure working on the Strelka’s sails. Both frigates had rendezvoused at the star bell, the last marker of civilization before the transition from Common Union territory to unexplored space. The Strelka was smaller than the Sovereign, but newer, lighter, and faster. She was on her way to another assignment but had obligingly stopped at the star bell when requested to do so by the Sovereign. Though the Sovereign was the older of the two ships, many of her crew members were new to the Fleet and were in need of training by the Strelka’s more experienced crewmembers.

And none more in need of training than I am, Elsa thought. Life aboard the Fleet frigate was not at all what she had expected.

By twisting her neck hard to her right, she could just get a glimpse of the star bell behind her. The spindle-shaped bell was dwarfed by the larger frigates, but it caught the eye nevertheless. The star bell was old, older than the Fleet; the bells had been placed at the boundary more than a century ago by the Fleet’s precursors, explorers setting out from the first colonies. As the boundaries were expanded, the bells were pushed back to encompass the new territory. The bell tolled a radio wave frequency that told everyone with a receiver within range where the boundary lay, and a bright pulse of light shone out from its center, providing a visual reminder. This close to the bell, the light almost seemed to be an audible brightness, affecting both senses.

She turned back to the sail, swallowing hard and working on controlling the nausea. Turning her head to look behind her hadn’t helped the situation. She fixed her gaze ahead and tried not to think about the nightmarish possibility of vomiting inside her spacesuit, which quickly became all she could think about. The star bell’s light alternately threw her shadow against the sail in front of her and whisked the shadow away as the light pulsed from the old beacon.

Elsa sighed. She had to admit it to herself: she was miserable in the Fleet. This was no place for her. She knew she couldn’t waltz in and expect to get a propulsion job right away, but she had yet to even meet most of the engineering crew, let alone begin studying with them. She was used to hard work and long hours, but there was no joy in her experiences aboard the frigate.

Part of her discomfort with the situation was caused by how freakishly seamless her teammates’ transitions to their new lives seemed by comparison. Bruno was doing a poor job of hiding his glee at being back on a Fleet ship, with intermittent fits of brusqueness when he remembered why he left in the first place. He didn’t seem to be letting his guilt hold him back from embracing his new role as bosun, though.

Gus took to Fleet life with unsettling ease, and by the second day was completely unruffled by the relative opulence that made so many of the other cinders uncomfortable. He already had a wide network of acquaintances and casual friends among the Fleet crew—but then, Gus could make friends anywhere.

Jaq was smitten with Marraine, and getting a word out of him on any other subject was nearly impossible. Elsa had noticed a shadow flit across his face a time or two, however, and she suspected he was a little bit homesick and wouldn’t admit it. She almost hoped that was the case, just to have someone to commiserate with, but they hadn’t had a chance to discuss it. Jaq spent nearly every waking moment with Marraine.

As for Marraine herself, the fay was like a bird deprived of flight its entire life that had suddenly been released into the skies. She practically danced across the sails, managing to make the clunky magnetic boots look like the lightest of slippers. She would be out on the sails for double shifts if they let her. Aboard ship, Elsa knew she was marginally less at home. She seemed perpetually chilled, and snuggled in her Fleet-issue long coat as though it were an oversized blanket.

Elsa would not admit that any part of her unease was caused by Karl Tsarevich. He had done nothing to make her feel uncomfortable; on the contrary, he had been nothing but courteous and inoffensive since she came on board. Perhaps that was the problem. Mild politeness did not exactly equate with romantic interest, and she couldn’t shake the occasional sense of horror when she thought of how boldly she had assumed he was interested in her when he offered to bring her and the other ex-cinders aboard. Well. Boldly for her, anyway, unaccustomed as she was to such things. Now, for better or worse, she was stuck on the same ship with Karl for a year. As big as the frigate was, it would feel awfully small if this awkwardness continued as they both danced around each other.

Her conscience was assuaged by the self-knowledge that, attraction for Karl or not, she had not taken this job because of him. Far more important to her than the fledgling possibility of a romance was her cinder family and the chance to pursue a dream she had thought long dead.

She set her jaw. Karl or no Karl, space-sickness or no space-sickness, she wasn’t going to give up.

“Nearly there, Elsa,” said a silvery voice through the commline in Elsa’s helm.

Her thoughts had provided a welcome distraction from her acrophobia, and Elsa was able to relax her fixed stare on the sail to look about for the approaching fay.

Marraine flew into Elsa’s field of vision and alighted on the yardarm like a hummingbird landing on a branch.

Elsa huffed in disgust. “Rub it in, why don’t you?” she groused, but her heart rate was already slowing, having an ally nearby.

“Bruno explained that you were—scared?” Marraine seemed puzzled by the notion that someone could possibly be afraid of traipsing across the sails like they were her own private playground.

“Yes,” Elsa said grimly. “I’m scared. Now help me down from here, will you?”

Marraine tilted her helmed head. “It’s not really down from here, you know, there isn’t a down in space—” She cut herself off, seeing Elsa’s glare. “Um, never brain. May I have your hand?”

“It’s ‘never mind,’ ” Elsa said, forcing the fingers on her right hand to unclench themselves from around the halyard. She snatched at Marraine’s hand and held it tight.

Marraine frowned as she felt Elsa’s grip. “Really? Why?”

A trickle of sweat was making its itchy, slow way down the side of Elsa’s face, and she couldn’t do anything about it with her helmet on. “No idea,” she gritted out, tense again at the prospect of having to move from her position, which felt almost secure after maintaining it so long.

“You have to let go with your other hand,” Marraine reminded her patiently, nodding to Elsa’s left hand still clutching the halyard.

Elsa made the grave error of looking up at Marraine, with all that empty space behind her. “I know. I’m just not sure that I can.” Panic stood up and trampled all other thoughts. Her palms were sweaty, but the gloves gave her a good grip; letting go seemed suicidal.

“Yes, you can, Elsa Vogel.” Marraine didn’t often scold, but there was a hint of exasperation in her voice. “Here, close your eyes and I’ll guide you. Just focus on placing one foot at a time.”

Elsa shook her helmed head and instantly regretted it. Marraine was sweet, but she didn’t understand this sort of terr

or. Elsa wanted so badly to be useful she could almost taste it—or was that the nausea?—but she didn’t know how to overcome her own trepidation.

“Tell me a story,” Elsa said desperately. Distraction had helped her before.

“What?” Marraine asked, startled.

“Just—just tell me a story. Tell me about Hayzeltry. Tell me what you had for breakfast. I don’t care, just talk to me.”

Marraine was looking at her in wonderment, clearly unfamiliar with this particular brand and intensity of fear. How nice for her, Elsa thought, but managed not to make any nasty remarks out loud. She always had lashed out when she was afraid. Better to attack than show vulnerability. But that trait didn’t tend to endear one towards one’s friends, she had been told.

“I will not be a burden,” she said, breathing too fast. “Distract me long enough to get me down. I want to work closer to the main hull where I can pretend there’s a floor.”

“Of course,” Marraine said in her musical voice. Elsa focused on that peaceful sound.

She let go.

She flailed wildly for a moment, but Marraine’s thin, strong fingers squeezed her hand as she began to tell her story and the two women began to move. “You’ve never been to Hayzeltry, of course—almost no one has,” the fay said. “The first Fleet ships came to our world when I was growing up, and then after the attack near our world that began the Cendrillon Wars, it was decreed that no Demesne or Common Union forces could come near the planet until the Wars were over. And even then, it was written into the peace accords: no one could exploit us for labor, no one could experiment on us. We were to be left to ourselves, unless we wanted otherwise, but we had to be the ones to make contact.”

Elsa listened to Marraine’s slightly alien, hypnotic voice and did her best to block out every other sensation. It didn’t work—her head still whirled with dizziness—but she moved along the halyard, and she did so under her own power. “For our part, we knew almost none of that at the time,” she interjected, remembering how her parents hadn’t been sure the fay planet even existed. “They kept your world such a secret for so long.”

The Battle of Castle Nebula (The Cendrillon Cycle Book 1)

The Battle of Castle Nebula (The Cendrillon Cycle Book 1) The Star Bell (The Cendrillon Cycle Book 3)

The Star Bell (The Cendrillon Cycle Book 3)