- Home

- Stephanie Ricker

The Star Bell (The Cendrillon Cycle Book 3) Page 2

The Star Bell (The Cendrillon Cycle Book 3) Read online

Page 2

Marraine’s expression was unreadable. “They tried. That was the state of things, anyway, until the ship we’re walking on now came to my world,” she continued.

Elsa glanced at her and hissed out a breath of air as she accidentally caught sight of anything more nausea-inducing than her own feet—namely, the space behind Marraine. “The Sovereign came to Hayzeltry?” She dimly recalled Karl mentioning that he had been to the fay homeworld once, but the significance hadn’t struck her at the time. Only since becoming friends with Marraine had she realized the true extent of the intricate political dance that was even now happening around Hayzeltry and its inhabitants.

Marraine nodded, regarding Elsa unblinkingly as she guided her down the halyard. “Oh yes. Although of course I didn’t know the ship’s name at that time; it was the first ship of its kind that I had seen. And your Karl doesn’t know it, but he did meet me there, briefly.”

Her reference both flattered her and gave her a twinge of uneasiness. “He is not my Karl,” Elsa declared. Curiosity overwhelmed emotional ambivalence. “How in the worlds did you two meet?”

Marraine gave her a look that plainly said she wasn’t falling for distraction tactics, but would take the moral high ground by withholding comment. “The Sovereign was at the outer edges of Common Union space, and Demesne ships had boxed her in. She broke through at last, hiding in the asteroid belt just beyond my world. So long was she there, though, that her crew began to run out of protein sources. They couldn’t just land a frigate on our world to resupply, though—such an act would have been a violation of the agreement with the Demesne that both sides would leave us be.”

“So what did Captain Tsarevich do?” Elsa asked, interested in spite of herself.

Marraine chuckled, a liquid, bell-like sound. “He’s quite bold, our captain. He took a skiff that was in line for repair for a defective engine, and he personally flew it into Hayzeltry’s atmosphere. The skiff’s engine couldn’t handle the forces, and of course our gravity sucked it down. It landed in one of our rivers. I imagine it was a rough downtouch,” she added.

Elsa shook her head. “You mean ‘touch-down.’ I can imagine.” Rough was an understatement. Tsarevich was lucky to be alive. Boldness was one thing, but some would call such a move plain stupidity.

“He happened to land in the river not far from where I lived, and my friends and I saw the plume of water. We climbed on our riverwhales and swam out—”

“Wait, what?” Elsa had been counting the remaining steps until her boots touched the main hull, and Marraine’s words took a moment to register. “Your what? How big is this river?”

Marraine gestured with her free hand. “Oh, from here to there.”

Elsa followed the movement, quelling her rebellious stomach. “From here to the end of the sail?” she asked in disbelief.

Marraine laughed her silvery, carillon laugh. “No, no! From here to just past the Strelka.”

Elsa gazed across that distance against her better judgment. “I begin to realize,” she said slowly, “that I know remarkably little about what life must be like on your planet.”

Marraine smiled. “That is true, my dear.” Her voice changed in timbre. After a moment, Elsa realized what the tone was: wistfulness. “It’s warm—I miss that. Rivers cut through everywhere, but we have huge forests of silvery trees. Their leaves are green on one side, silver on the other, so they look like they’re twinkling when a breeze blows, and a breeze is always blowing. The sky is full of birds that move in a large group. I don’t know what you call that?” She looked questioningly at Elsa.

“A flock?” she suggested.

Marraine shrugged. “It could be. Sometimes the groups are so large, they darken the sky.” She made a face Elsa had never seen on her before. “Lots of excrement to clean up afterwards.”

Elsa chuckled.

Marraine resumed her story. “Anyroad, we swam out to the skiff and retrieved poor Captain Tsarevich, who was unconscious but otherwise unharmed. It was best that he wasn’t awake for the trip; when we told him later that he had ridden a riverwhale, he seemed quite upset.”

“Fancy that,” Elsa said, shutting her eyes tightly for a moment against another wave of panic caused by staring across at the Strelka. “What’s a riverwhale?”

“Oh, I’m glad you asked,” Marraine said eagerly. “Riverwhales are beautiful. They’re slender, furred creatures that spend most of their time in the rivers. They’re the loveliest color.” Marraine frowned. “What’s the word for grey-green?”

Elsa opened her mouth, then shut it. “I…don’t think there is one.”

Marraine looked miffed. “There is in my language, and that’s the color of the riverwhales. They’re very easily domesticated. Almost everybody has at least one, and some people keep whole herds. They’re our main means of travel.”

Elsa squinted, trying to picture the strange-sounding creature. “Sounds more like an otter than a whale,” she said dubiously. “How big are they?”

Marraine considered. “In length, from here to the hull.”

Elsa estimated that distance at seventy or eighty feet, which was entirely too far for her present liking. “Sun and stars, that’s massive.” She wanted to know more about the animals, but she struggled to catch the thread of the story again. “So you took the captain back to land aboard your otter-things. Then what happened?”

Marraine gave her a sidelong glance at “otter things” but again refrained from commenting. “When he awoke, we took him to our local council. His skiff couldn’t make it off the planet and back to his ship, obviously, so he made a plea to the council to allow his frigate to land to pick him up. He said that he would pay handsomely for such a privilege, and even more handsomely for any local food that we could supply. He promised that his ship would leave as quickly as possible. The debate on whether to grant his request was…extensive.”

From Marraine’s tone, Elsa suspected that the debate had been passionate indeed. That was no surprise; the only other encounter between the fay and offworlders had been profoundly negative.

“At last, the council agreed, and the Sovereign landed—quite a sight for those among us who had never seen a ship so large, as you may imagine!” Marraine looked over shyly. “I was rather smitten. Seeing the ship was what gave me the idea to explore. We gathered the supplies that the captain had requested, but we didn’t yet know of your sensitivity to radiation. The difference isn’t enough to harm you if you were on our world for a few days,” she added, “but the sailors had to be careful how much of our food they ate, as it turned out. The sailors loaded the supplies, and the captain introduced his son Karl. Many of the ship’s children had a meal with us—poor things, they were all so hungry—before returning to their newly provisioned ship. They left quickly, as the captain promised, and they were the last outlanders we saw on our world for a long time.”

Elsa was only half-listening by the end of the story as the end of their journey grew closer. At last, her boots touched solid hull. With a mighty sigh of relief, she unclipped her lifeline from the halyard and retracted it. She stood taking deep breaths, calming herself down.

Marraine was still watching her curiously, uncomprehending. “Do you ever feel scared like that when you’re in a ship?” she asked. “Particularly a skiff or something small?”

Elsa refrained from shaking her head this time, deciding not to push her luck. “No, never. Not sure why. I guess if I’m in a craft of some kind it doesn’t bother me.” She had been unable to come up with any other plausible reason, but she was profoundly glad she didn’t have to go through this every time she was in a small ship. She looked at her friend. “Thank you, Marraine. I’m so grateful for your help. You did more than you realize.”

Marraine smiled. “You’re welcome.”

“I want to hear more about your world one day soon,” Elsa told her. “One day when I’m not battling nausea and can greater appreciate magical tales of riverwhales, whatever those are.” S

he looked around cautiously. “For now, where do you think I should set up? I want to at least try to pull my own weight.” If she thought too much about her failure aloft, she grew too angry with herself.

“Are you sure you want to stay out here?” Marraine quirked a skeptical eyebrow at her, a trait Elsa was fairly sure she had picked up from Bruno.

“Yes.” Elsa’s tone brooked no argument. “I’ll check in with Bruno to see what needs doing on this level.” She suddenly remembered she had left her ditty case magnetized to the yardarm and swallowed her pride down with some difficulty. “Could you please go back and get my ditty case? Then I’ll let you get back to your work. I know you’re due aloft.”

“Certainly,” Marraine replied. “They really don’t need me yet. I’m still a trainee so there are other topmen and women on the shift.” Marraine was training to do the trickiest work at the furthermost ends of the masts. Elsa tried not to be envious of how quickly Marraine was learning, without much success.

“Back in a moment,” the fay said, and she took off, using her maneuvering thrusters to zip along the halyard up to the yardarm where they had begun.

Elsa heaved a sigh and tried to rub the side of her face against her helmet to catch that blasted drip of sweat. She was unsuccessful. She connected to the bosun’s commline. “Bruno?”

“Hey,” he responded almost instantly. “I was keeping an eye on you. You did good. Looks like you’re back on solid hull. Heading inside?”

The stubborn set of Elsa’s jaw was back. “No. I want to work. Is there anything I can do down here?”

Bruno hmm’ed to himself, presumably looking over the data coming through his bosun’s station. “Well, one of the Strelka riggers is finishing up his current task. I can send him over to train you on configuring the zero-point energy funnels on the gunwales, if you’re interested.”

Elsa perked up. This, at least, she knew a little about. She had always been fascinated by propulsion. Her mother had taught her a good deal before she died, and she had gone through the Fleet’s prep program as a teenager, hoping to work in that field. “That would be perfect! Thank you, Bruno.”

“No problem, girl,” Bruno replied, and Elsa warmed to the fatherly affection in his voice. Bruno, Marraine, and the rest of her friends made the fear tolerable. Barely.

Marraine swooped in, Elsa’s ditty case in hand. “Here you are!” she said, far too cheerfully to Elsa’s grumpy ear.

“Thanks,” Elsa replied, snagging the case from her. Marraine didn’t even stop moving; her maneuvering thrusters were already shooting her sail-ward when she tossed a quick, “You’re welcome!” over her shoulder. Her glee was almost palpable, and it made Elsa’s mood worse.

Bruno spoke again into her ear. “Should be just a second. The Strelka rigger is on his way over to show you the ropes.”

Almost before Bruno had finished speaking, Elsa caught a streak of movement from the corner of her eye.

The daredevil rigger who had been working farther up the sail when Elsa was paralyzed by fear zoomed past her, landing on the main hull ahead of Elsa with a silent thump.

“Show off,” Elsa muttered. This was her trainer? She was thankful that energy collectors were sedate, matronly parts that didn’t require any acrobatics to repair.

The rigger spun adroitly and strode across the hull towards Elsa. “You the new girl who’s space sick?” he asked via helm commline. He was a good deal taller than Elsa—though most people were—but she couldn’t see much of his face. From here, the Sovereign’s sail shielded them from the star bell’s light pulse and cast them into shadow.

Elsa fumed silently at Bruno. Fatherly affection, her foot. Fatherly teasing was more like it. There was no reason for him to tell the Strelka rigger she was about to puke in her helmet. “Aye,” she replied shortly. “And you’re here to teach me about configuring zero-point energy collectors. Now that we’ve got the obvious out of the way, perhaps you could show me to them?”

At her testy tone, the rigger put his hands up in placation. “Hey, sorry, just wanted to make sure I had the right person. Follow me.” He turned and moved towards the Sovereign’s gunwale, the slight thickening of the ship’s main hull that provided the extra strength to support the conduits for the large energy collectors.

Elsa winced. Don’t make enemies unnecessarily, she told herself. When her fear did the talking, it tended to have a sharp tongue. She shuffled after the other rigger as quickly as she dared, still being mindful of her rebellious stomach.

The rigger knelt down at one of the panels set into the gunwale, magnetizing his ditty case to the hull plating. Elsa eased down to her knees on the other side of the panel across from the rigger, ignoring the slight whoosh of dizziness as she did so.

She tried to make peace before the encounter went any further off course. “Sorry,” she offered. “Having a bad day.”

The rigger waved her off with a gloved hand. “I had the same problem with space sickness when I started.” He pulled a marlinspike from his ditty case and tapped it against the panel to unlock it. The panel detected the tool’s energy signature, and a light flashed blue next to it.

Relief unspooled inside her, releasing some of the tension. “Really! Oh, I’m so glad to hear that,” she said fervently.

The rigger laughed as he slid the panel door open. Something about his chuckle seemed vaguely familiar to Elsa, but she couldn’t place what it reminded her of. “You’ll get used to it,” he assured her. “I just hadn’t been loose in space much before I took the job.”

“Me neither,” Elsa confessed, peering inside the open panel. The delicate system of collector filaments running through the sails came together into larger and larger arteries, finally forming thick cables that ran beneath the gunwale into the heart of the ship. “But if you went from being sick to jumping from sail to sail like a cat, so can I.”

The rigger laughed again. “Eh, I’m more of a dog person.”

Elsa narrowed her eyes. Now where had she heard a laugh like that before? “Oh, me too,” she told him. “I had a whole pack of them growing up.” She leaned closer. “So what is it we need to do?”

“We need to take readings on the energy flow through the funnels and make sure they’re within parameters,” he said, rummaging in his case for an anemometer to scan the collectors. “If anything’s not flowing properly, we may need to replace a portion of the filament.”

Elsa squinted inside the panel. The interior lighting inside the panel was woefully inadequate, and she could hardly see the filaments. “It’s black as space in there,” she complained. “Didn’t think to bring a light in that case of yours?”

“Someone’s too smart by half,” the rigger grumbled, “but there’s a light on your helm.” He activated his own by voice command.

Elsa looked up into the now-illuminated faceplate of the rigger. She shot to her feet, regardless of nausea. “Godfrey?” Her voice rose an octave in shock.

The rigger also stood, dropping his marlinspike, which bounced gently against the hull with the movement and rebounded back away from the plating. Elsa reached out and caught it without thinking.

“Elsa!” the rigger sputtered. “What in the worlds are you doing here?”

Elsa stared at his face: older, surprisingly lined, but unmistakably that of her childhood friend from Anser. “I could ask the same of you! The last time I saw you, you were back on Anser with no plans to leave. I thought you’d be there forever.” She didn’t say it, but that thought had been a comfort to her—that no matter what happened to the rest of the galaxy, Godfrey and his hunds would remain as they were, traversing the snowfields.

Godfrey hitched one shoulder upwards in an awkward shrug. “Things changed. It was time to leave. But you were a cinder, last I heard. Or am I misremembering?”

Elsa felt a pang of guilt over not having contacted her childhood friend in so long. “No, you’re right; I was a cinder for nine years. Long enough to pay off all of my debts,” she add

ed, with just a hint of bitterness. She studied the marlinspike in her hand to avoid meeting his eyes. “I’m sorry I never sent you a message. Mining was hard at first, and there didn’t seem to be time. And then…there were so many bad memories of the time of my leaving. Maybe I was a little afraid of reminding myself of them.” She finally met his glance. “I know that’s no excuse,” she said, resisting the urge to shirk that responsibility.

His face held only kindness, though: no resentment. “I understand. Those were rough days for everyone, but rougher for you than for most of us.” He paused. “I missed you, though.”

The tinge of vulnerability in his voice made her guilt wake up, yawn, and stretch, ready to go again, but Bruno’s voice over her commline interrupted her. “Elsa? You okay? I’m still reading that the panel in front of you is open, but the line isn’t cleared yet.”

Elsa shook herself, and she and Godfrey knelt in front of the panel again. “Sorry, Bruno, we’re getting started now. I met an old friend, and we were just catching up.”

“Really? Oh.” Bruno sounded shocked, and small wonder; Elsa had never really talked about any friends other than her cinder team. Talking about her past dredged up so much pain; she usually just didn’t. Until Karl asked her about it at the dance on Aschen, she hadn’t talked about her parents’ death in years.

“We’ll finish up soon and come in,” Godfrey added. “This won’t take long.”

“No worries,” Bruno said. “We’re not in a rush today.” There was no chastisement in his tone, but Elsa felt a little sheepish anyway. She hadn’t been the most productive worker today.

Godfrey quickly showed Elsa how to re-calibrate the cables, checking them afterwards with the anemometer to make sure the energy was flowing properly. Elsa was relieved to find that it wasn’t that difficult after all—one of the few things she had encountered in her new life that wasn’t difficult. Energy flow made sense to her, and it felt good to use skills she thought she’d never have use for again after she became a cinder. Her stomach had settled, and when she stood to go back inside the Sovereign, she realized she hadn’t felt panic at all in quite a while. She and Godfrey walked across the hull to the nearest hatchway, feeling the odd sucking sensation of the magnetic boots with every step.

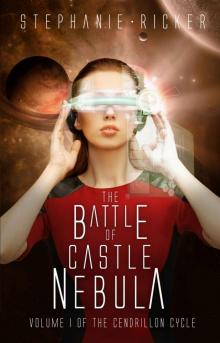

The Battle of Castle Nebula (The Cendrillon Cycle Book 1)

The Battle of Castle Nebula (The Cendrillon Cycle Book 1) The Star Bell (The Cendrillon Cycle Book 3)

The Star Bell (The Cendrillon Cycle Book 3)